In our last in-depth article, we dived into the world of food waste; its social, economic and environmental implications, but also the new avenues we can explore today in order to change the story we will tell our guests – and the world – tomorrow.

We took a closer look at the issue of food waste because, due to our production and consumption habits, it has become a problem too big to ignore – also from a moral perspective.

However this, as we all well know, is only part of a much wider and complex issue.

With no pretention of extensively covering all the corners that exist, we suggest taking a step back and looking at the mess we are all in and seeing where we could start the clean-up.

Waste relevance

First and foremost, what are we looking at?

According to data provided by the World Bank, the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) annually, of which at least 33% is not managed in an environmentally safe manner.

In the study ‘What a Waste 2.0 – A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste management‘ from the same source, it calculated that if no improvements are made, the amount of ‘emissions from solid waste treatment and disposal are expected to increase to 2.38 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year by 2050’, from the previous 1.6 billion tonnes, estimated in 2016.

Also, according to the World Bank, 12% of global waste is plastic waste, including plastic packaging. According to United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), of the 146.1 million US tons of MSW going to landfill in the United States in 2018, plastics were the second-most-common type of material sent there, after food (24%).

We are seeing our oceans being polluted by waves of plastic, and the National Geographic reports that without any substantial changes in the model of production, consumption and waste management that we currently adopt, by 2040 almost 30 million metric tons of plastic will end up in the ocean per year, sadly tripling the amount in which turtles and dolphins currently swim.

The heaviest

According to Plastic Oceans, 50% of global annual plastic production is intended for single-use purposes, of which tourism is a large consumer.

Although there are other kinds of solid waste, plastic is probably one of the first words that we associate with it, and among the most stressful factors for the environment. In fact, according to UN Environment Programme (UNEP), ‘plastics are the largest, most harmful and most persistent of marine litter, accounting for at least 85 per cent of all marine waste’.

Even though global awareness of the problem won’t solve it on its own, and despite the massive contribution that our industry generates towards the global problem, we can help by taking action and joining initiatives like the Global Tourism Plastics from the One Planet Network. It ‘aims to stop plastic ending up as pollution while also reducing the amount of new plastic that needs to be produced’ and is open to businesses, destinations, associations and NGOs.

The avoidable

When considering plastic waste, packaging represents an abundant and unnecessary percentage of the single use plastic that is emitted into the market.

According to a report by the World Economic Forum, ‘plastic packaging is plastics’ largest application, representing 26% of the total volume of plastic used’.

Eurostat reports that ‘between 2010 and 2020, the volume of plastic packaging waste generated per [EU] inhabitant increased by 23% (equal to more than 6.5 kg)’; and although they report that in 2020, several countries including Netherlands, Slovakia, Spain, and Cyprus, recycled more than half of their plastic packaging waste, there are still many others than recycle less than one-third, including Malta, France and Denmark. Although there is still lots of work to do on the recycling side, we should also keep looking for greener alternatives.

According to data presented by Wrap.org ‘the world produces 141 million tonnes of plastic packaging a year’, a third of which becomes a pollutant for the environment.

Not all countries have the same production and consumption habits, though.

In the UK, for example, the amount of plastic packaging placed on the market is 2.3 million tonnes, which accounts for a massive 70% of UK plastic waste. However, even bad habits can be eradicated, with the right action.

The signatories of the UK Plastic Pact – a national movement that has extended globally and one of the voluntary agreements launched by Wrap – demonstrated an 84% reduction in problematic and unnecessary single use plastics since 2018. They have also achieved an inspiring rise in recycled content levels from 8.5% in 2018 to 22% in 2021, accompanied by a rise in the quantity of recyclable plastic packaging used, from 66% to 70%.

The greenest

For the public, as well as for the industry’s stakeholders, tackling plastic packaging does not necessarily need to be a Herculean effort, but could start with small but considered choices: the choice of the right business partners, for example, or the right inspiring conversation with a supplier on your ‘greener’ purchasing preferences. These are the decisions that will greatly affect the industry in the long term.

Reuse and refill stores, for example, are becoming more and more popular preferences among consumers, and we hope to see the same trend grow steadily in the tourism supply chains as well.

In any case, the scene is changing and the need for more sustainable procurement has already started. The importance of green supply chain management is expected to grow, both to meet customers’ expectations, and sometimes simply to improve business performance and cut costs. The need to integrate new sustainable environmental processes into the traditional supply chain will affect aspects such as product design, material sourcing and selection, manufacturing and production, and overall operations.

The newest

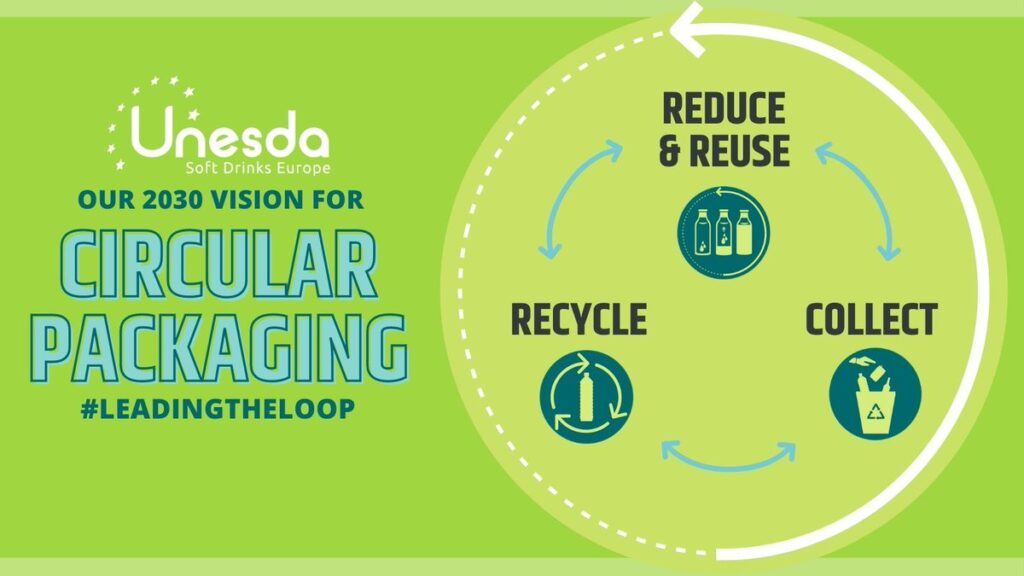

A promising initiative has been presented by UNESDA, who represent the European soft drinks industry. Last year the association launched a project to introduce full circularity to beverage packaging.

With the initiative Circular Packaging Vision 2030, presented in February 2021, they support ‘a closed-loop beverage packaging collection and recycling system’ and aim to reach 90% collection of beverage packaging of aluminium cans, glass bottles and PET bottles, by 2030.

In addition to investing in research on efficient refillable models, they are looking at the goal, by 2025, of using only 100% recyclable packaging for aluminium cans, glass bottles and PET bottles, or PET bottles that use at least 50% rPET.

Waste hierarchy

An important question regarding this topic is how we look at the issue, meaning which actions should we give priority to?

To structure our response, we have borrowed the waste hierarchy approach (in the image below) provided by the Waste Framework Directive, used as the foundation of EU waste management.

It is a common opinion that the ‘prevention’ stage – during which the product is still a product, and it hasn’t turn into waste yet – should guide our actions.

The ‘disposal’ stage, on the other hand, should be treated as the last resort, having implemented the other solutions first, so that ideally its use is always avoided, or at least reduced to a minimum.

Let’s have a brief look at the two extremes of this hierarchy, for some brief considerations.

PREVENTION

When thinking in terms of waste prevention, it has been recognised that ‘lack of information and guidelines, time constraints, space and finance’ can represent barriers and negatively influence investment at this stage.

However, if we look at the benefits, there should be no doubt about why our attention is being focused here.

Looking at the results of the research ‘Best Environmental Management Practice in the Tourism Sector – 6.1 Waste Prevention’, presented in 2017 by the European Commission, the evident environmental benefits also translate into a series of incentives to action, defined as ‘driving forces’ to prevent waste.

Environmental responsibility, however, which should drive the performance of any kind of business anyway, has not always been ‘activated’; legislation is also listed as another force, although its power of influence, of course, varies by country and region of the globe. Other important motivations are related to cost reduction, in particular waste disposal costs, waste handling costs and excess product costs for partially used products and unnecessary packaging.

It might be interesting to analyse how many of these have already been ‘triggered’ in your company – why, and with what results.

DISPOSAL

Although it is positioned at the bottom of our hierarchy triangle, we shouldn’t underestimate the danger that inadequate waste disposal can create for the environment in terms of toxic chemicals released into the water and soil, and the strain that it puts on landfill and sewage plants.

Waste management is a general problem for urban environments and islands, that can be felt more intensively by those destinations that are the tourists’ favourites, and at risk of over-tourism.

It is valuable to bear in mind that the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that one guest can generate from 1 to 12 kg of solid waste per day when visiting a new place while worldwide, according to World Bank data, waste generated per person per day ranges widely from 0.11 to 4.54 kg.

One emblematic case – among many others – is the Greek island of Paros, which is becoming the first plastic-free Mediterranean island, thanks to the Clean Blue Paros’ initiative from Common Seas.

One of the biggest motivators to act for change was the massive increase in waste that the island used to suffer during the summer months, when it would grow by up to 350%.

Waste collection and disposal, as well as the reduction of single-plastic use, have been efficiently tackled thanks to the coordinated efforts of local government, private businesses, community members and associations.

This is not the only case where a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) has proven its effectiveness in the resolution of waste management problems.

Changing mindset

As we have highlighted several times, we strongly believe that even before taking new actions – and, in fact, in order to make these very actions part of the DNA of any business – the mindset towards the issue must change.

Sometimes the mindset changes during practice in the field, while working and realising that things can be done in other ways; sometimes having realised there are inefficiencies in the way we operate, we start consciously looking for new answers, and dare to try different, sustainable innovations.

Sometimes change happens because we are inspired by others’ examples and achievements, which also prove that more is possible.

Sometimes, though, our mindset might start changing because we have taken the time to listen and engage with new thoughts or information.

We are proud to have several changemakers in our community, providing inspiration by using and implementing alternative solutions on their premises.

One of them is Amilla Maldives Resorts and Residences that, among its numerous sustainability projects, has opted for producing in-house many of the food items used for meals – such as jam, kombucha, probiotic sodas and coconut oil, among others, this avoids producing additional packaging waste from importing the same.

Others offer services that support businesses so making the changes is simpler and more effective, like the case of Travel Without Plastic and their LRSU Toolkit. This was specifically created to encourage the hotel industry to make a smoother transition towards more sustainable choices with a greater value and respect for the environment.

We are also happy to include and support initiatives that aim to achieve positive impact by continuously working on raising awareness – with the general public as well as within the industry – like the case of the Make Travel Matter campaign by Travel Matters, that has recently joined the other members of our growing community.

Although all the above is true and possible, we don’t have the luxury of leaving the opportunity (to change) to luck. That’s why we should always consciously and responsibly adopt a proactive approach towards change, perhaps from a systemic perspective.

Words by Elisa Spampinato

Recent Posts

Categories